Sales of A-brands in Dutch supermarkets fell sharply in 2024. The headline number drew attention across Europe, but for buyers and suppliers working inside the market, it confirmed something already visible on shelf.

The Netherlands has become one of the most demanding grocery markets for branded FMCG. Private label is strong across almost every tier. Retailers run disciplined ranges. Shoppers switch quickly. There is very little patience for products that do not earn their place.

This is not a market where brands disappear overnight. But it is a market where relevance is tested constantly.

The 2024 sales drop is a signal, not a single-year anomaly

The reported decline in A-brand sales was shaped by regulation, pricing pressure, and range disruption. Tobacco’s removal from supermarkets distorted topline numbers, but even without that factor, many core brands struggled to hold volume.

More importantly, the drop exposed structural stress that has been building for years.

-

Shoppers are spending more selectively

-

Fresh food is taking a larger share of the basket

-

Price sensitivity is high

-

Private label quality is no longer a compromise

In the Netherlands, value does not always mean “cheap”. It means justified. Brands that cannot explain why they cost more are increasingly questioned by both shoppers and buyers.

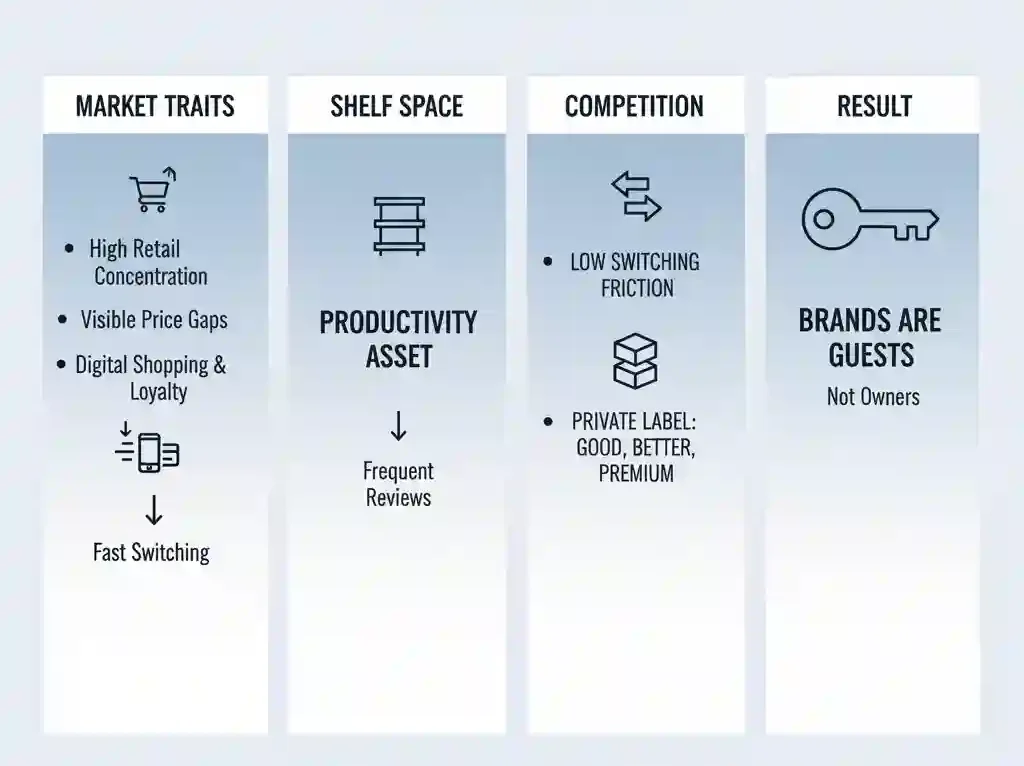

Why the Netherlands is especially tough on brands

Several market traits combine to make the Dutch environment unusually hard for A-brands.

Retail concentration is high. Range decisions are centralised. Price gaps are visible. Online and app-based shopping are mainstream. Loyalty schemes are deeply embedded in weekly shopping behaviour. Alongside private label growth in the Netherlands, this has created a market where switching is fast and brand loyalty is constantly tested.

This creates a market where:

-

Shelf space is treated as a productivity asset

-

Ranges are reviewed often, not protected by history

-

Switching friction is low

-

Private label competes across good, better, and premium

In simpler terms, brands are guests on the shelf, not owners of it.

Shelf space is negotiated every year

For Dutch buyers, shelf space must justify itself commercially. This is where how Dutch supermarkets control shelf space becomes visible in day-to-day range decisions.

An A-brand keeps its listing when it does at least one of the following:

-

Grows the category, not just its own share

-

Brings shoppers the retailer struggles to reach

-

Delivers reliable volume and supply

-

Funds activity that lifts total sales

-

Supports the retailer’s price and quality architecture

Heritage alone is rarely enough. Even long-established brands are expected to perform like new ones.

This mindset explains why disputes between retailers and suppliers have such visible consequences in the Netherlands. When negotiations fail, products leave the shelf. When products leave the shelf, shoppers adapt fast.

Availability matters more than brand love

Dutch shoppers are pragmatic.

If a brand is missing, they replace it. Often with private label. Sometimes with a competing brand. The longer the absence, the weaker the return.

From a buyer’s perspective, this changes the risk calculation. A brand that causes disruption creates work, complaints, and uncertainty. A private label alternative often does not.

This is why operational reliability has quietly become one of the most important “brand strengths” in the Netherlands.

How A-brands defend space today

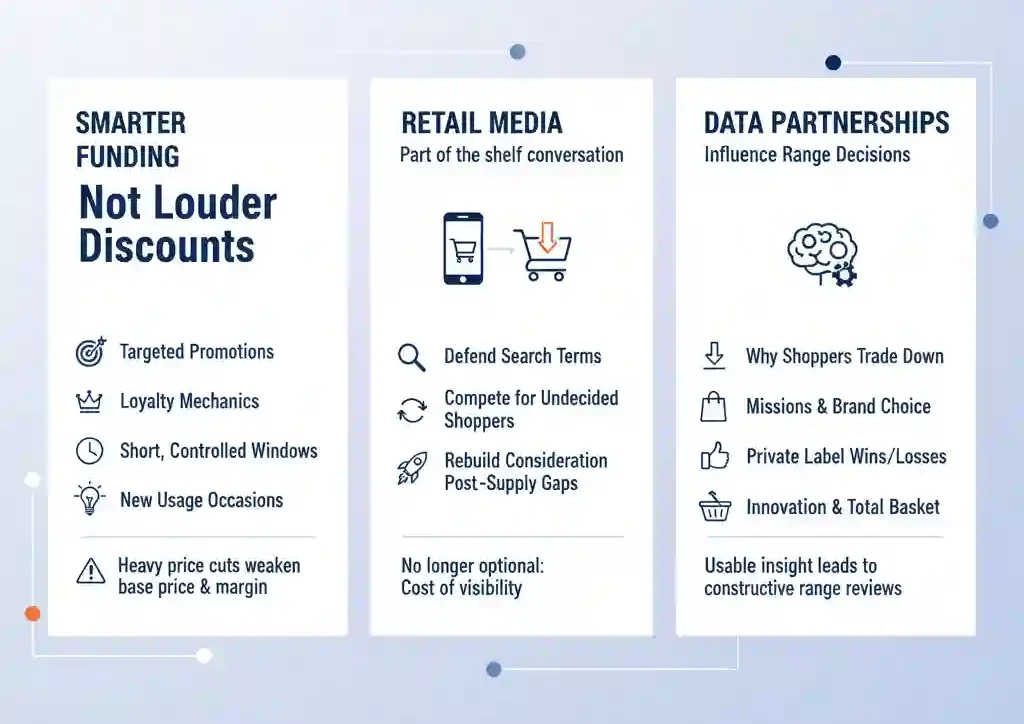

Smarter funding, not louder discounts

Promotions still matter, but their role has changed.

Repeated deep discounts reduce credibility and train shoppers to wait. Buyers increasingly look for activity that changes behaviour, not just timing.

That includes:

-

Targeted promotions instead of blanket deals

-

Loyalty-based mechanics

-

Short, controlled promotional windows

-

Activity tied to new usage occasions

Brands that rely entirely on heavy price cuts often weaken their base price and long-term margin — for themselves and the retailer.

Retail media is now part of the shelf conversation

Digital visibility has become inseparable from physical availability.

In a market where a large share of shoppers plan, search, or check offers through apps and webshops, being listed is not the same as being seen.

Retail media allows brands to:

-

Defend branded search terms

-

Compete for undecided shoppers at category level

-

Support new launches with proof of performance

-

Rebuild consideration after supply gaps

For many brands, retail media spend is no longer optional. It has become part of the cost of remaining visible in a high private-label market.

Data partnerships influence range decisions

Retailers increasingly value suppliers who help them understand shopper behaviour.

Not theory. Not slides. Practical insight.

Examples include:

-

Why shoppers trade down in a category

-

Which missions still trigger brand choice

-

Where private label wins — and where it doesn’t

-

How innovation affects the total basket

Brands that contribute usable insight often gain more constructive conversations during range reviews, even when sales are under pressure.

Where A-brands still win in the Netherlands

Despite the pressure, brands remain relevant in specific zones.

Innovation speed

Brands typically innovate faster than private label. New flavours, formats, or functional variants appear first through A-brands.

That advantage only lasts if repeat purchase follows. If not, private label will catch up.

Trust-led categories

In baby, infant nutrition, and sensitive personal care, trust still matters. Shoppers may try private label, but reassurance remains a key factor.

Execution failures are costly here. One quality issue can undo years of brand equity.

Performance-driven categories

In homecare and hygiene, perceived performance still gives brands space. But claims must be credible, consistent, and easy to understand.

“Works better” must feel real, not marketing-led.

Category-by-category trade reality

Beverages

Brands remain strong, driven by impulse, habit, and innovation. Sugar-free, functional, and convenience formats help defend space.

However, high promotional intensity risks weakening long-term value perception.

Ambient grocery

This is the most difficult battleground.

Private label quality is high. Price gaps are clear. Switching costs are low. Mid-tier brands are under constant pressure.

Brands that survive tend to do one of two things:

-

Premiumise clearly

-

Own a specific taste or usage moment

Those that sit in the middle struggle most.

Baby and toddler

Still brand-led, but unforgiving. Availability, compliance, and communication must be flawless.

Price matters, but trust matters more.

Personal care

Brands benefit from habit and performance perception. Private label continues to improve, especially in basics.

Digital shelf presence increasingly decides which brands stay visible.

Homecare

Brands win when performance is obvious and proven. Tiered brand strategies tend to perform better than single hero SKUs.

Why disputes hurt more in the Netherlands than elsewhere

Dutch shoppers do not wait.

When a brand disappears due to a dispute, substitution happens quickly. The replacement often works “well enough”. The longer the absence, the weaker the emotional pull when the brand returns.

For suppliers, this makes confrontation riskier than in slower-switching markets.

For retailers, it reinforces confidence in private label as a safety net.

What buyers are watching heading into 2026

Across the market, buyers are paying closer attention to:

-

Supply reliability

-

Clean pricing structures

-

Reduced promo dependency

-

Digital execution quality

-

Innovation that clearly earns space

Brands without a clear role are increasingly vulnerable during range reviews.

What the Dutch market is really doing

The Netherlands is not rejecting A-brands.

It is filtering them.

Brands that adapt — commercially, digitally, operationally — continue to win listings. Those that rely on past strength alone steadily lose relevance.

For suppliers, the Dutch market is not a warning sign. It is an early indicator.

Conclusion

The decline in A-brand sales in 2024 is not just a bad year. It reflects how competitive the Dutch grocery market has become.

Private label is strong. Retailers are disciplined. Shoppers are pragmatic.

A-brands can still succeed — but only by proving their value every day, on every shelf, physical and digital.

That is how branded FMCG competes in the Netherlands today.

Editor’s note

This article is based on publicly reported Dutch supermarket sales trends, observed retailer–supplier dynamics, and category-level trade behaviour across European grocery markets. No confidential retailer data or unpublished statistics were used.