For years, shelf space in supermarkets was shaped by brand power. Strong A-brands secured listings through recognition, marketing investment, and shopper trust. That balance has shifted. Private label is no longer a secondary option sitting at the bottom of the shelf. It is now central to how retailers manage categories, margins, and long-term control.

As private label expands, A-brands are being forced to defend shelf space in new ways. The fight is no longer about branding theory or awareness alone. It is about how shelf space decisions are made, what brands are willing to trade, and whether they still fit the commercial logic of modern grocery retail.

How shelf space decisions are made today

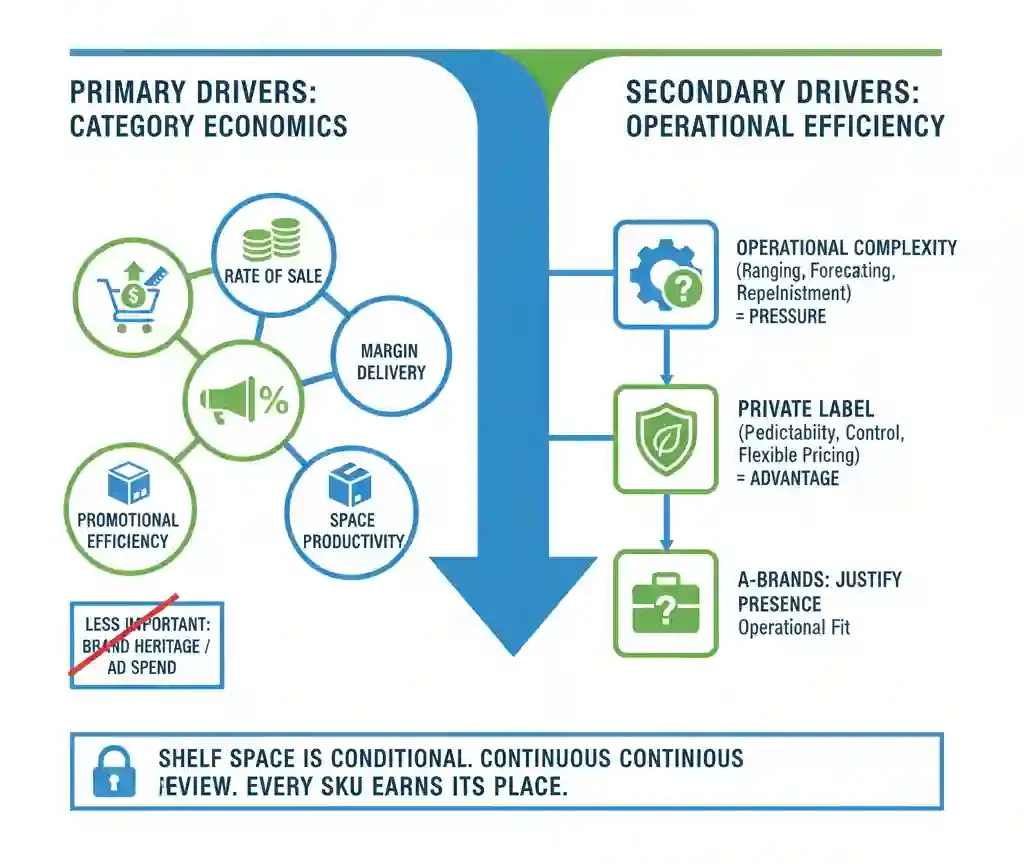

Shelf space decisions are now driven by category economics rather than brand status. Buyers look at how each product performs within the system of the category, not how well known the brand is outside the store. Rate of sale, margin delivery, promotional efficiency, and space productivity all carry more weight than heritage or advertising spend.

Retailers also assess operational complexity. Products that complicate ranging, forecasting, or replenishment face increasing pressure. In contrast, private label offers retailers predictability and control, with clear cost structures and flexible pricing. A-brands must now justify their presence in a way that fits this operational mindset, not just a marketing one.

This is why shelf space has become conditional. It is reviewed continuously, and every SKU is expected to earn its place.

The reality of range rationalisation

Range rationalisation is no longer a temporary measure linked to inflation or supply disruption. Retailers have learned that tighter assortments can improve shopper clarity and increase overall category performance. As a result, tolerance for duplication and low-performing variants has fallen sharply.

For A-brands, this means fewer second chances. When SKUs are removed, they rarely return. Buyers are prioritising clarity over choice, and private label often fills gaps more efficiently than multiple branded alternatives. Brands that once relied on breadth now have to focus on relevance.

Range discussions are no longer about how many facings a brand deserves. They are about which products genuinely add value to the category.

What A-brands actually trade to protect shelf space

Despite these pressures, A-brands still retain influence. But that influence comes from what they trade in practical terms, not from reputation alone.

Trade spend remains important, but its role has narrowed. Buyers increasingly favour fewer, well-funded promotions with clear objectives and measurable outcomes. Constant discounting without strong performance data is viewed as inefficient and is often a reason for delisting. Brands that can show how their trade spend grows the category, not just their own volume, are more likely to hold space.

Data sharing has become just as important. Retailers expect brands to contribute insight into shopper behaviour, basket dynamics, regional performance, and promotional learning. Brands that actively share usable data strengthen their position in range and category discussions. Those that keep insight internal weaken their relevance. Private label already gives retailers full visibility, so branded suppliers must now compensate through transparency.

Retail media has also become a defensive tool. Investment in on-site advertising, digital shelf placements, and retailer platforms supports both visibility and traffic. From a buyer’s perspective, brands that invest in retail media are supporting the retailer’s ecosystem, not just negotiating for space. This added value increasingly plays a role when shelf decisions are reviewed.

Why some brands survive while others lose ground

The brands that manage to defend shelf space tend to share common behaviours. They accept that smaller, more focused ranges are often more sustainable than wide portfolios. By concentrating on core SKUs with clear roles, they reduce internal overlap and simplify buyer decisions.

They also stop treating private label as an enemy to be defeated. Retailers are not choosing between brands and own label; they are balancing both. Brands that acknowledge this reality and position themselves alongside, rather than against, retailer own brands tend to remain relevant. This aligns closely with how private label strategy now shapes category planning across most major supermarket groups.

Most importantly, surviving brands understand category logic. They speak in terms of shopper missions, space productivity, and total category performance. Buyers respond to this language. Brands that focus only on their own story, without linking it to the wider category, are easier to replace.

The new reality for A-brands

Shelf space is no longer owned. It is effectively rented.

That rent is paid through margin clarity, data contribution, media support, and operational simplicity. Private label has raised expectations across all of these areas, and those expectations are not going away. A-brands that adapt to this reality can still play a meaningful role on the shelf. Those that rely on past strength or emotional arguments continue to lose ground quietly.

What happens next

Over the next 12 to 24 months, pressure on branded shelf space is likely to increase. Retailers will continue to simplify ranges, expand private label into mid-price and premium tiers, and demand greater transparency from suppliers. Retail media will replace parts of traditional trade spend, and data sharing will become a baseline requirement rather than a differentiator.

This shift reflects a broader change across the FMCG industry, where predictability, control, and system efficiency increasingly outweigh brand scale alone. A-brands will not disappear, but their role will keep evolving. Those that understand how shelf space is now defended will remain visible. Those that do not will gradually be designed out of the shelf.