Supermarket operating models are changing faster than store formats because the pressures forcing change are internal, structural, and immediate. Labour costs, margin compression, and operational complexity now determine how supermarkets must function long before they decide how stores should look. The visible retail format lags because it is not where the business risk sits. The operating model is.

What shoppers see on the shop floor often feels stable. What suppliers and internal teams experience behind the scenes is anything but.

Why Operations Change First

Operating models change first because they sit closest to cost, control, and risk.

Labour is the most direct driver. Wage inflation, staff shortages, and tighter employment regulation have transformed labour from a flexible variable into a fixed constraint. In the past, store managers absorbed shocks by adjusting rotas, leaning on experience, and making local trade-offs. That model breaks down when labour is scarce, expensive, and scrutinised.

From head office, variability becomes a problem. Two stores with the same sales profile can show very different labour costs depending on local decisions. That variability is no longer tolerable when margins are thin. The response is not to redesign stores, but to redesign how labour decisions are made.

Labour planning shifts from judgement to system. Hours are allocated centrally. Productivity targets are standardised. Exceptions require justification. This is not about mistrust of stores. It is about reducing exposure.

Margin pressure reinforces this shift. Grocery margins have always been narrow, but rising input costs, permanent price competition, and promotional intensity leave little buffer. When margin is tight, inconsistency becomes expensive. Supermarkets respond by tightening governance, not by experimenting with formats.

Complexity is the third force. Modern supermarkets manage wider ranges, deeper private label portfolios, stricter regulatory obligations, and more fragile supply chains than they did a decade ago. Each additional SKU, supplier, and compliance rule adds friction. Local decision-making multiplies that friction.

Operating models evolve to cope. Buying decisions are centralised to reduce duplication and improve leverage. Range logic is standardised to control sprawl. Pricing rules are encoded into systems rather than negotiated store by store. These changes do not require a new shop layout. They require new rules.

This is why operating model change happens quietly. It is driven by necessity, not ambition.

Internal Decision-Making Has Shifted

A key change many external observers miss is how internal decision-making itself has been restructured.

Supermarkets now operate with longer planning horizons and tighter approval gates. Budgeting cycles are more rigid because forecasting accuracy matters more than local optimisation. Deviations from plan are harder to justify because the system assumes consistency.

Decision latency has become a cost. In complex environments, slow or fragmented decisions create risk. Centralisation reduces debate, but also reduces flexibility. Supermarkets accept that trade-off because predictability now matters more than local responsiveness.

This is also why negotiations feel different to suppliers. Decisions take longer because they run through systems and committees. Once made, they are harder to reverse because they are embedded in operating logic rather than personal relationships.

The operating model is designed to reduce surprise.

Why Store Formats lag Behind

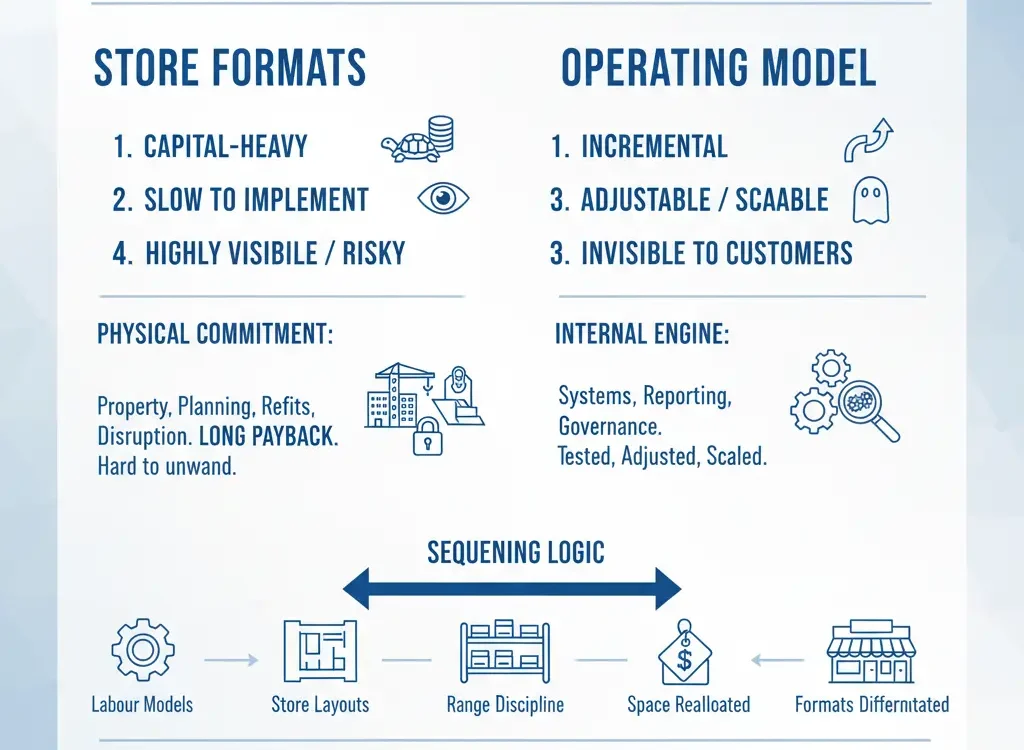

Store formats change last because they are capital-heavy, slow to implement, and highly visible.

Changing a format means committing to physical expression. It involves property teams, planning permission, refits, customer disruption, and long payback periods. It also locks the retailer into a strategic direction that is hard to unwind.

Operating model changes are different. They can be rolled out incrementally through systems, reporting lines, and governance. They can be tested, adjusted, and scaled without customers noticing.

There is also a sequencing logic at work. FFs want the internal engine to be stable before redesigning the body around it. Labour models need to be understood before store layouts change. Range discipline must be proven before space is reallocated. Pricing logic must be trusted before formats are differentiated.

This is why formats appear static even as the business underneath is transformed.

To shoppers, the store still looks familiar. To suppliers, the rules of engagement have already changed.

Formats Reflect Decisions Already Made

When store formats eventually change, they rarely introduce new thinking. They reflect decisions that were made earlier inside the operating model.

A smaller format is often the consequence of tighter range logic, not a creative leap. A simplified layout usually follows labour constraints, not design ambition. Reduced local variation reflects centralised control, not a loss of interest in customers.

By the time a format changes, the strategic decision has already been taken. The store is catching up with the system.

This is why observers who focus only on visible change often misread the pace of transformation. They look for new concepts and miss the fact that the operating model has already shifted.

Centralisation Is Not A Trend

Centralisation is often described as a trend. In reality, it is a structural response to scale and risk.

Decentralised models work when systems are simple and margins allow slack. In today’s environment, decentralisation creates fragmentation. Fragmentation drives cost, weakens pricing discipline, and increases operational exposure.

Centralised buying reduces supplier count and range duplication. Centralised pricing protects margin architecture and limits price leakage. Centralised labour planning improves visibility and reduces both over-staffing and under-staffing.

This does not mean stores are irrelevant. It means their role has changed. Stores execute within a tighter framework rather than shaping it. Value creation has moved upstream, closer to data, systems, and financial control.

Importantly, centralisation also changes accountability. Performance is measured against system benchmarks rather than local context. This can feel harsh at store level, but it aligns the business around fewer variables.

Why Formats Resist Rapid Change

There is another reason formats lag behind: customer tolerance.

Shoppers adapt slowly to format change but quickly to price, availability, and service failures. Supermarkets prioritise fixing the invisible issues first because those issues directly affect availability, pricing accuracy, and execution.

From a risk perspective, it makes sense to stabilise operations before asking customers to adapt to new layouts or missions. Format change becomes safer once the operating model can support it.

This is also why format change often looks conservative. By the time it happens, the business is optimising rather than experimenting.

What This Means For Suppliers

For suppliers, the implications are significant.

Influence has shifted away from the store and toward the system. Relationships still matter, but they operate within tighter constraints. Decisions are less personal and more rule-based.

Suppliers feel this as tougher negotiations, clearer conditions, and lower tolerance for exception. Listings are increasingly conditional on operational fit, not just sales performance. Data quality, supply reliability, and margin contribution carry more weight than history.

At the same time, the environment becomes more predictable. Once suppliers understand the operating logic, they can plan more accurately. The challenge is that many still sell as if stores control outcomes.

The real decision-maker is now the operating model.

Strategic Implication

The strategic implication is not that store formats no longer matter. It is that they are no longer the starting point.

Supermarkets are changing from the inside out. Operating models evolve first because that is where cost, complexity, and risk must be controlled. Store formats follow later, once systems and economics are aligned.

The mistake is to judge transformation by what is visible. The real change has already happened — quietly, internally, and structurally.

Understanding that sequence is what separates surface commentary from real insight.

Editor’s note: This article is based on industry reporting, public financial disclosures from major supermarket groups, trade press coverage, and structural analysis of grocery retail operating models. It reflects sector conditions and decision-making patterns observed up to October 2023.