This shift toward a smaller circle of suppliers is not accidental and it is not temporary. It is a strategic move known as supplier rationalization, sometimes called supply base reduction. While it can look risky from the outside, retailers are increasingly choosing depth over breadth to manage the growing complexity of modern grocery retail.

The logic is simple. Managing fewer suppliers makes it easier to control risk, cost, compliance, and execution across thousands of stores and millions of transactions.

As a result, fewer suppliers are now winning a larger share of supermarket contracts. This is not driven only by mergers and acquisitions. It is driven by how supermarkets now operate.

Supplier Rationalization as a deliberate strategy

Supplier rationalization is a conscious decision by retailers to reduce the number of suppliers they work with and deepen relationships with those that remain.

In the past, supermarkets often believed that having many suppliers increased competition and protected supply. In today’s environment, that same structure creates complexity that is expensive and difficult to manage.

Modern grocery retail operates across multiple pressures at once. Price competition is intense. Margins are thin. Regulation is expanding. Supply chains are more fragile than they appear. Every additional supplier adds another layer of administration, risk, and oversight.

Retailers are responding by simplifying their supply base. Instead of managing dozens of suppliers per category, they focus on a smaller group that can integrate deeply into their systems and processes.

This approach allows supermarkets to shift from transactional buying to strategic partnerships. The goal is not just to buy products, but to secure stable, predictable supply that works across pricing, logistics, compliance, and long-term planning.

Resilience Over Price After Supply Chain Shocks

The supply chain shocks of 2020 to 2022 changed how supermarket buyers think.

During that period, many retailers discovered that managing large numbers of small suppliers became a liability rather than a strength. When disruptions hit, coordinating dozens of suppliers across different regions, standards, and capabilities created delays and uncertainty.

Empty shelves were not always caused by lack of supply. They were often caused by lack of coordination.

In response, retailers began prioritising resilience over headline price.

They started favouring strategic partners who could guarantee continuity, even under stress. This meant working with suppliers that had the financial strength to invest in backup capacity, alternative sourcing routes, and private logistics infrastructure.

Larger suppliers are better positioned to do this. They can hold safety stock, operate multiple production sites, and reroute supply when one channel fails. Smaller suppliers often operate closer to their limits and have fewer fallback options.

For supermarkets, avoiding empty shelves is more valuable than shaving a small amount off unit cost. Price still matters, but it no longer outweighs the risk of disruption.

This shift explains why scale now wins contracts that price alone once secured.

Efficiency And Cost Savings From Consolidation

Supermarkets operate in a low-margin environment. Even small inefficiencies add up quickly.

Managing thousands of individual supplier contracts creates costs that do not appear directly on shelf prices. Each supplier requires onboarding, auditing, invoicing, forecasting, compliance checks, and ongoing performance management.

Reducing the number of suppliers reduces this administrative “tail”.

By consolidating supply, supermarkets gain stronger bargaining power. Buying a larger share of volume from one supplier instead of splitting it across many increases leverage in negotiations. This often results in lower unit prices, better terms, and more predictable cost structures.

Logistics efficiency also improves. It is cheaper to receive full truckloads from a single large supplier than to manage multiple partial deliveries from smaller ones. Fewer deliveries mean lower transport costs, simpler scheduling, and reduced warehouse congestion.

These efficiency gains matter because supermarket margins leave little room for waste. Consolidation helps retailers control cost across the entire operation, not just at the point of purchase.

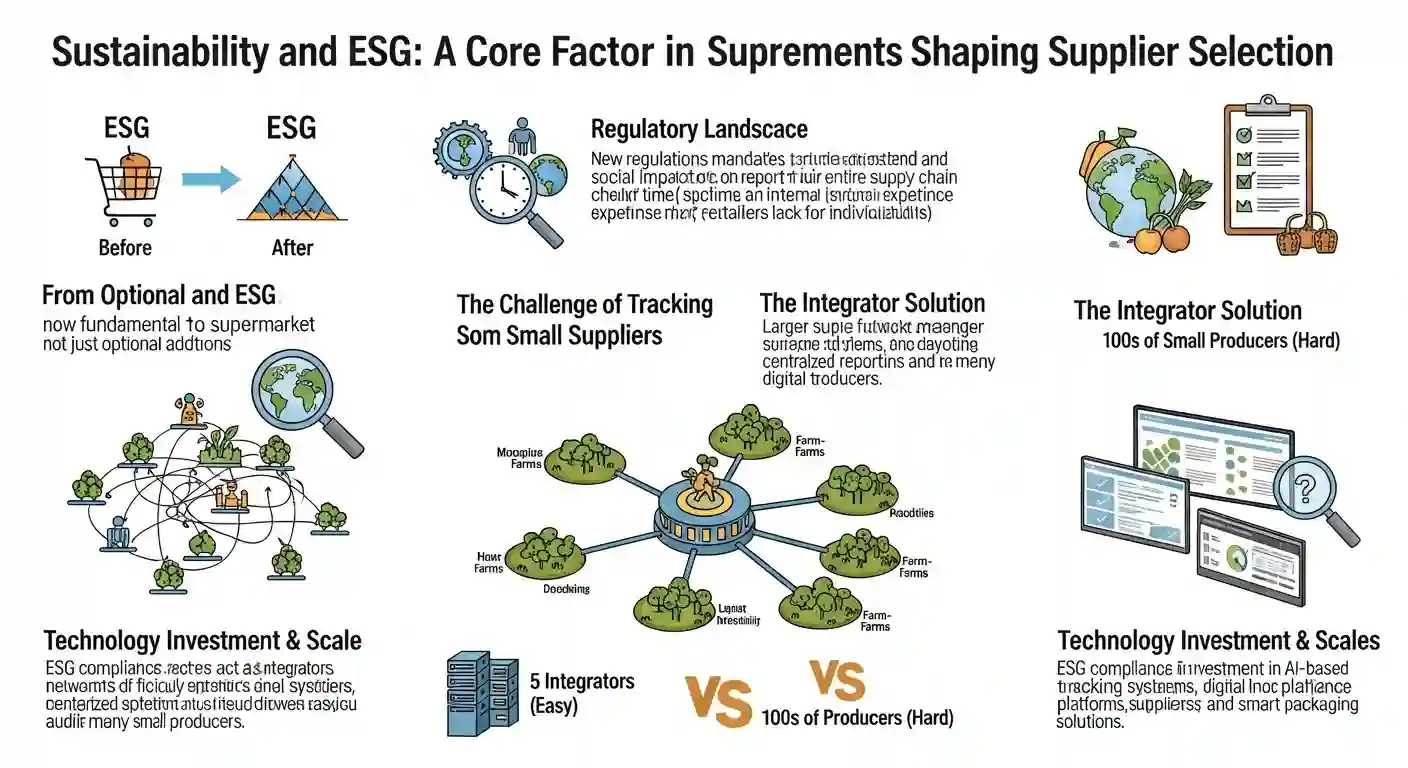

Sustainability And ESG Requirements Shaping Supplier Choice

Sustainability and ESG requirements are now core to supermarket operations, not optional add-ons.

New regulations require retailers to understand and report on the environmental and social impact of their entire supply chain. This includes carbon footprint, labour practices, and sourcing transparency.

Tracking this information across hundreds of small suppliers is extremely difficult. Auditing each one individually requires time, systems, and specialist knowledge that many retailers do not have internally.

Larger suppliers solve this problem by acting as integrators. They manage networks of farms or sub-suppliers and provide centralised reporting and digital traceability. For supermarkets, auditing five large integrators is far more practical than auditing hundreds of small producers.

Investment in technology also plays a role. AI-based tracking systems, digital compliance platforms, and smart packaging solutions require capital. Larger suppliers can fund these investments and align them with retailer requirements. Smaller suppliers often cannot.

As ESG obligations tighten, retailers increasingly favour suppliers that can deliver transparency at scale. This reinforces consolidation. This is also where packaging compliance and traceability become commercial issues, not just regulatory ones, which links naturally into your broader packaging coverage.

Private Label Growth Favouring large Manufacturers

Private label growth is one of the strongest forces behind supplier consolidation.

Supermarkets continue to expand their store brands because they offer higher margins, stronger price control, and greater flexibility than third-party brands. Private label also allows retailers to differentiate without relying on branded suppliers.

However, private label contracts come with demanding requirements. Retailers need manufacturers who can produce large volumes consistently across an entire country or region. Quality must be uniform. Supply must be reliable. Costs must stay tightly controlled.

Small manufacturers often struggle to meet these demands. Even when product quality is high, production capacity, consistency, and geographic coverage can be limiting factors.

Larger suppliers are better suited to private label production. They already operate at scale and can integrate private label manufacturing into existing operations. This makes them preferred partners as private label expands.

Over time, this replaces branded shelf space with retailer-owned alternatives and concentrates volume with fewer suppliers. This shift sits at the heart of how private label reshapes supplier selection.

Structural shift In How Risk Is Managed

Supplier consolidation reflects a deeper change in how supermarkets manage risk.

Traditionally, retailers relied on diversification. More suppliers meant more options if one failed. In practice, this created coordination challenges that increased risk rather than reducing it.

The modern approach focuses on strategic depth. Retailers choose fewer suppliers but integrate more closely with them. Risk is managed through shared planning, data integration, and aligned incentives.

Technology supports this shift. AI-driven demand forecasting, digital reporting, and real-time performance monitoring allow supermarkets to work more closely with a small group of partners.

This level of integration is difficult to achieve across a fragmented supplier base. It works best when both sides invest in the relationship.

As a result, consolidation is not simply about reducing numbers. It is about building systems that function smoothly under pressure.

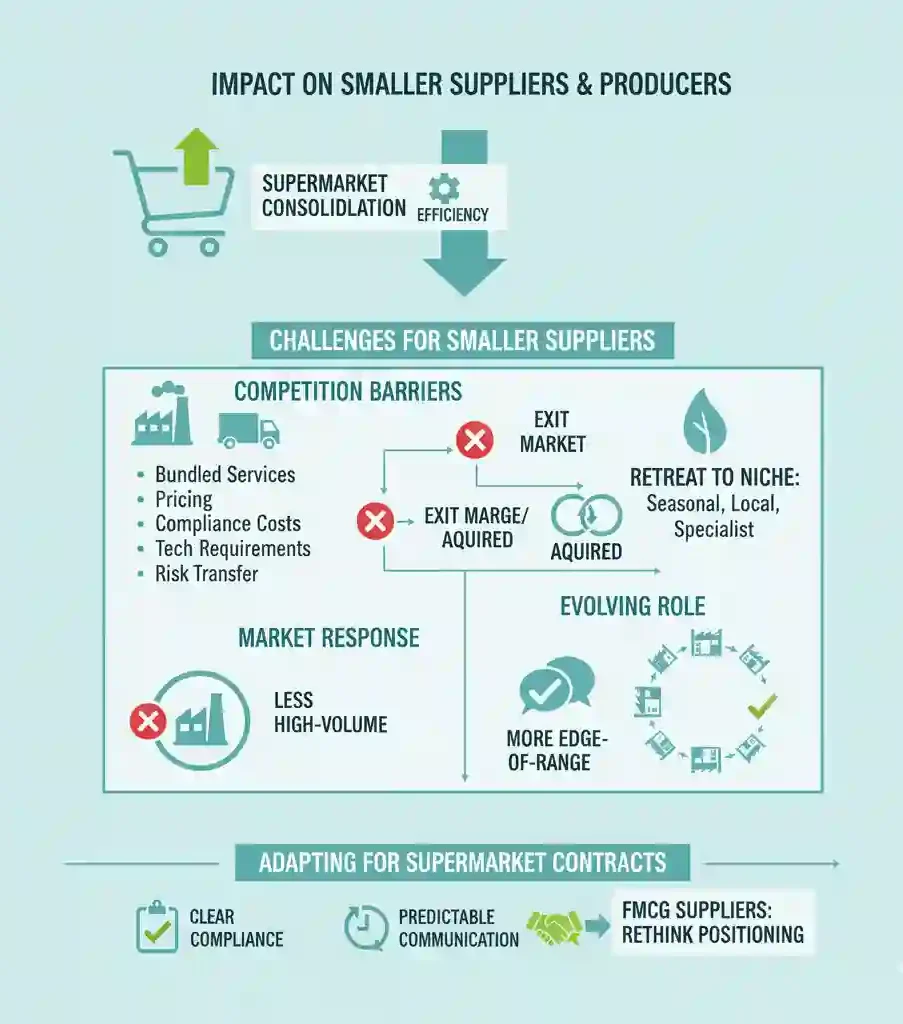

Impact On Smaller Suppliers And Producers

While consolidation improves efficiency for supermarkets, it creates challenges for smaller suppliers.

Many small-scale producers and local manufacturers struggle to compete with the bundled services and pricing offered by large suppliers. Compliance costs, technology requirements, and risk transfer all raise the barrier to entry.

Some small suppliers exit the market. Others merge or are acquired. Many retreat into niche roles, serving seasonal, local, or specialist segments where scale requirements are lower.

This does not mean small suppliers disappear entirely. It means their role changes. They are less likely to sit at the centre of high-volume categories and more likely to operate at the edges of the range.

For suppliers, adapting to this environment often means behaving like larger partners operationally. Clear compliance, predictable delivery, and simple communication become essential just to stay listed. This is where FMCG suppliers increasingly rethink how they position themselves for supermarket contracts.

Conclusion

Fewer suppliers are winning more supermarket contracts because supermarkets are deliberately simplifying their supply base.

Supplier rationalization reflects the realities of modern grocery retail. Thin margins, regulatory pressure, supply chain fragility, sustainability obligations, and private label growth all reward scale, integration, and resilience.

This trend is not about eliminating choice. It is about reducing friction.

As long as supermarkets prioritise efficiency and risk control, supplier consolidation will continue to shape who wins contracts and who is pushed to the margins.

FAQ

What are the disadvantages of supplying to supermarkets?

Supplying to supermarkets offers volume but comes with high pressure. Prices are tightly negotiated, margins are thin, and suppliers must absorb forecasting errors, compliance costs, and operational risk. Smaller suppliers often struggle with the imbalance of power and the constant threat of delisting.

Why are supermarket margins so low?

Supermarket margins are structurally low because grocery retail is highly competitive and price-transparent. Retailers face rising costs in logistics, labour, energy, and compliance but have limited ability to pass these costs on to shoppers. Volume and efficiency, not high mark-ups, drive profitability.

Why is the supermarket industry so competitive?

The industry is competitive because products are similar, switching costs for shoppers are low, and price comparison is easy. Retailers compete on price, availability, convenience, and private label strength, which keeps margins tight and operational pressure high.

What is the best reason for a company to use multiple suppliers for the same part?

The main reason is risk management. Multiple suppliers reduce dependency on a single source and protect against disruption. However, this approach increases coordination cost, which is why supermarkets now balance multi-sourcing with consolidation depending on category risk.